Hi everyone, best wishes as we all wait patiently through the COVID situation. What a challenging time for our leaders at home and abroad as they try to balance the trade-offs of personal health / safety versus damaging economic impact. I hope that everyone seeks to understand the data and subtleties on BOTH sides of this issue. However, what an appropriate time for quantum computing advancement that might bring new tools for R&D towards vaccination and related medical research.

Next Steps with Algorithms – Part 1:

As knowledge on basic principles of quantum computing and gate-level mechanics improves, the experience begs the questions “So what?” and “What next?”. With a little extra free time at home, I took some first steps in trying to understand basic principles of quantum algorithms, picking a copy of O’Reilly’s Programming Quantum Computers: Essential Algorithms and Code Samples.

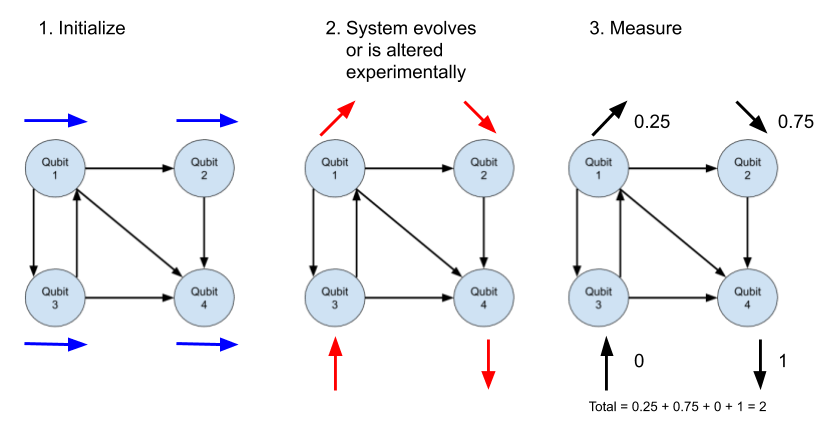

To get started, it’s useful to remind yourself of a few of the basic principles of quantum computing we’ve encountered so far:

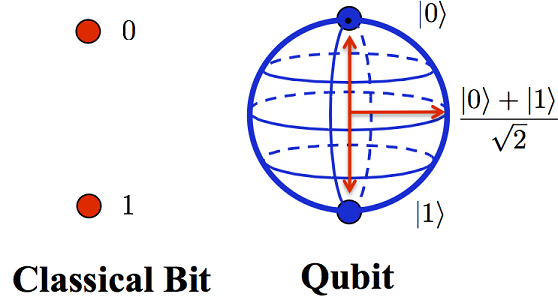

- Superposition: The property of a qubit to exist in a probabilistic state of 0 and 1. Aka “zero and one at the same time.” The best analogy I’ve heard is that of spinning a coin on a table. It’s neither heads nor tails until it stops. While spinning it’s both heads and tails at the same time.

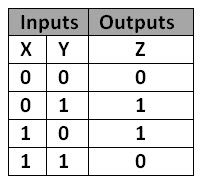

- Entanglement: The concept that the value of two (or more) qubits are directly related to each other, despite not being physically connected. This principle is particularly hard to believe as it defies logic in many ways, but has been proven to be true. The primary example is the simple controlled not (C-NOT) where the value of qubit A “controls” the value of the other.

- Reading a Qubit’s Actual Value Destroys the Superposition State: Both a useful property, such as in Quantum Key Distribution (QKD), and a limitation in that you can’t just “read” a qubit without losing information about the superposition state. That same spinning coin is either heads or tails once it stops, but not both.

I’m only about half-way through the book, but it’s a good time to relay some initial impressions. Initially, the book is written in a way that emphasizes learning of the algorithms vs the underlying math and physics. The approach has been helping in taking a next step in quantum learning, particularly as someone without a quantum physics background.

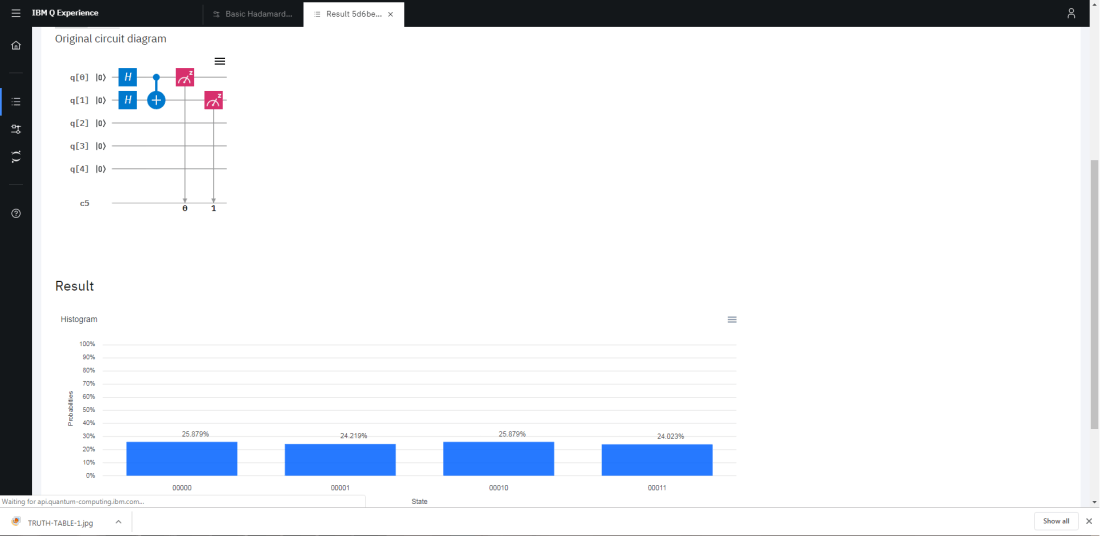

The immediate first take-away is perspective on using superposition with traditional binary logic or operations. This was an initial taste of what “zero and one at the same time” can do: multiple state solutions to a “problem” / circuit exist concurrently with a probabilistic rate of final occurrence. For example, suppose you have two 2-bit registers initialized to zero, and the second order bit in the second register is in superposition: ’00’ + ‘[0|1]0′. You have a certain chance of getting ’00’ (|0>) as the answer, and a certain chance of getting ’10’ (|2>).

Related, it became apparent qubit gates can be configured to achieve traditional binary techniques in the context of superposition (as described above). For example, bit shifting with Qubits: shifting all the bits to the left acts as a multiplication by 2. Brings back fond college homework memories.

Next, and the second major take-away from the book for me, the concept of qubit phase is introduced as a second method (behind 0 and 1) to encode information. To get an idea of this we need to revisit the Bloch Sphere and the concept of phase shifts in our good ole friend the sine wave…

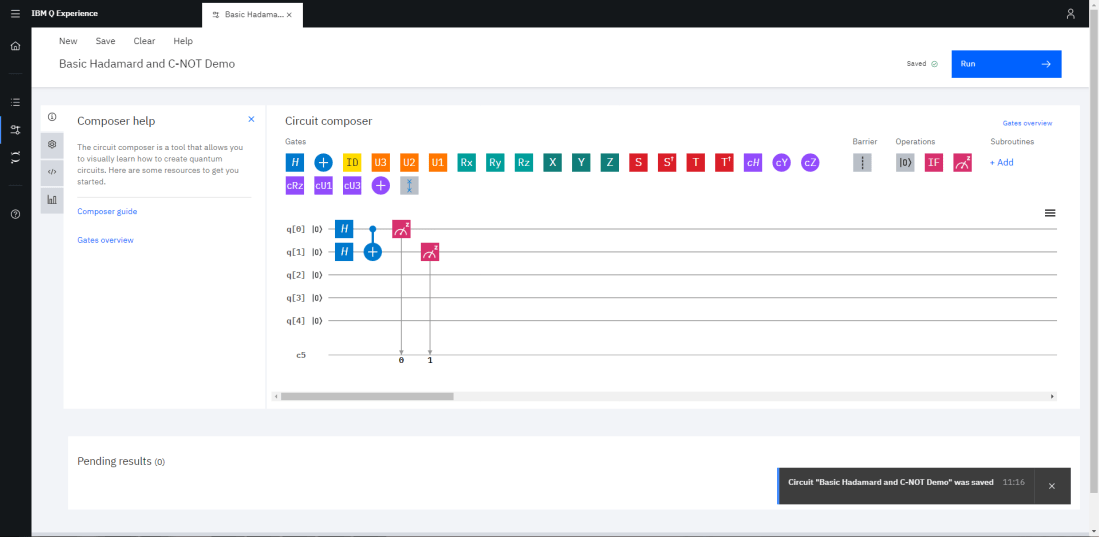

When we looked previously at the Block Sphere we considered the Hadamard gate placed the qubit in a superposition of |0> and |1>, which we specifically described (|0> + |1>) / √2. It became apparent that the ‘+’ part of that refers very specifically to the state that results from applying the Hadamard to a qubit initially in the |0> state. A Hadamard applied to a qubit in state |1>, on the other hand, results in a superposition state at the |-> position on the opposite side of the Bloch Sphere and implies a 180 degree phase shift in the qubit state. From there, many of the expected concepts of familiar signal processing processing / analog analysis begin to become apparent.

At this point it’s relevant to note that O’Reilly introduced a new visualization method (new to me at least) that incorporates the logical value of the qubit(s) (0 or 1) as a circle, the superposition state (probability of the value) as the amount of the fill of the circle, AND the phase as indicated by the line on the circle. Up for |+> state, down for |->. Here’s a quick snapshot.

Source: Programming Quantum Computers by Eric R. Johnston, Nic Harrigan, Mercedes Gimeno-Segovia

Source: Programming Quantum Computers by Eric R. Johnston, Nic Harrigan, Mercedes Gimeno-Segovia

In order to begin thinking about algorithms, a visualization such as this is required to go beyond simple binary state. So far, it’s been tremendously helpful for understanding the importance of basic phase concepts. While I don’t want to re-create the book, I do want to mention a couple key quantum primitives as take-aways thus far:

Amplitude Amplification: This technique takes a quantum register, where qubits are in superposition, with certain qubits in differing phase states, and converts the register to a corresponding state value that indicates those qubits that were in a unique phase. In other words, a phase shift finding algorithm. This method, which uses a technique called mirroring, is apparently a building block for future quantum algorithms.

Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT): Just like Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) from signal processing, frequencies in qubit register state values can be calculated directly. This is a useful primitive in future period finding algorithms. One that quickly comes to mind is Shor’s Factoring Algorithm, which is referred to frequently (pun intended) in early quantum reading as one that has quantum advantage, that leverages period as a sub-task to finding prime number factors. A quick look-around in the chapter titles confirms this. I’m looking forward to reaching those.

Again, you can buy the O’Reilly book here: Programming Quantum Computers.

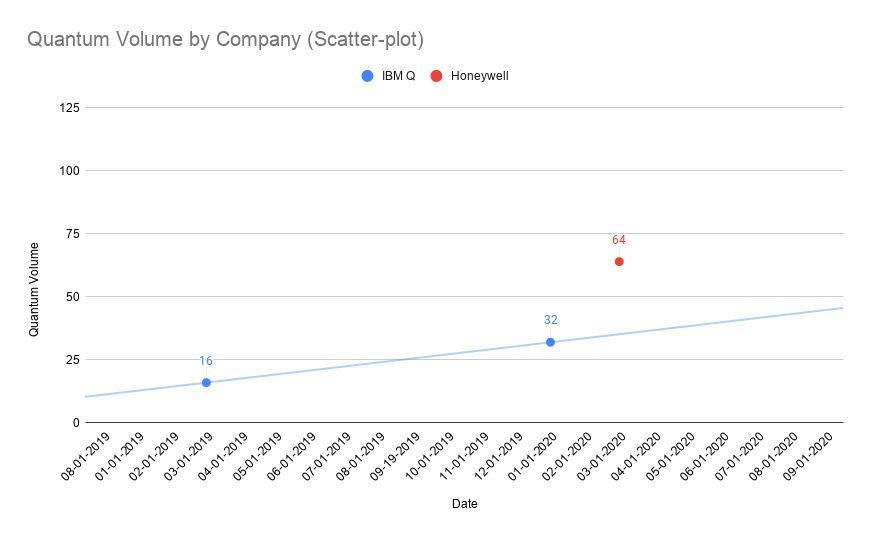

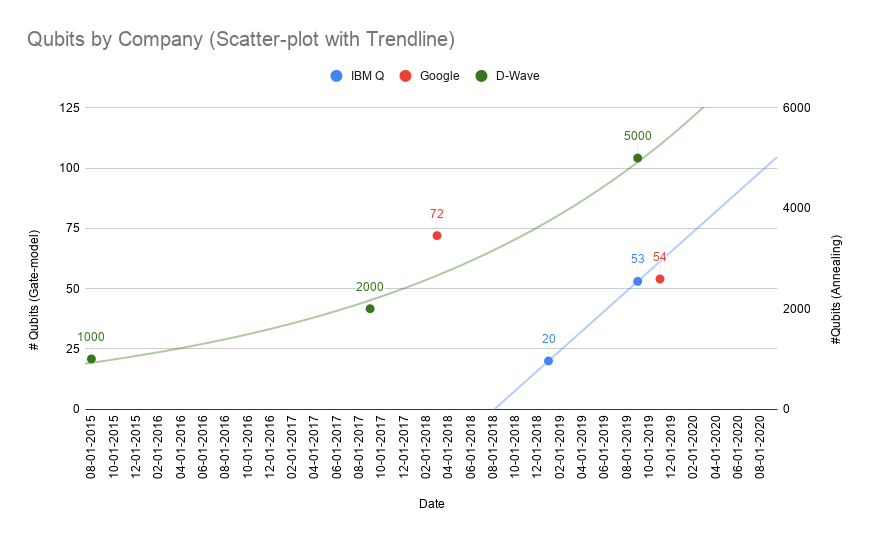

Industry Updates: Honeywell, D-Wave

Honeywell – New provider for IBM Qiskit: In my previous post, I spent a decent amount of attention on the buzz coming out of Honeywell that they had (or at least will) be releasing the fastest QC to date. And as part of that post, Microsoft will be offering Honeywell as a back-end to their quantum service. Overall I was left with the impression Honeywell, with their tech being based on Trapped Ion qubits, would be a distinct competitor to IBM; however, I read a surprisingly “quiet” announcement that a Honeywell provider for qiskit had been released. Sure enough, here it is. Another step towards major providers (IBM in this case) offering multiple back-ends to their service.

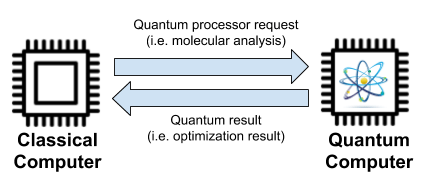

D-Wave – Leap 2 Launched (in February, sorry I’m just getting to it): One announcement I breezed by was D-Wave releasing their second generation development environment – Leap 2. It includes a refreshed, python-based IDE, which uniquely includes a hybrid solver services, that “automatically runs problems on a collection of quantum and classical cloud resources, using D-Wave’s advanced algorithms to decide the best way to solve a problem.” Very cool. It’s worth checking out their 30min overview; however, the example portion in the second half will be more meaningful if you have quantum programming experience – more than I have, I’ll admit I wasn’t able to follow the examples very well.

Quantum & COVID-19:

I’ll end on a couple quick COVID-19 notes. Hopefully the day is around the corner that quantum computing could potentially assist pharmaceutical research in quickly developing vaccines. In the current situation, quantum companies have been opening their doors to medical personnel as needed with easy / free access to quantum platforms as well as data & quantum techniques. There hasn’t been to be a lot of specifics currently on directly contributing success; however, the collaboration to help those closer to the front lines is inspiring. Here’s a few articles for reference.

Quantum Computing inc. Supports State & Local Governments with COVID-19 Data

National Science Foundation Taps Clouds for Quantum Computing Research (including Amazon, IBM, and Microsoft)

D-Wave gives anyone working on responses to the COVID-19 free cloud access to its quantum computers

Inside the Global Race to Fight COVID-19 Using the World’s Fastest Supercomputers

** This was by far my favorite article. Written by Dario Gil, Director of IBM Research, it ends with:

Humanity has more tools at its disposal in this pandemic than ever before. With data, supercomputers and artificial intelligence, and in the future, quantum computing, we will create an era of accelerated discovery. The consortium is an example of a unique partnership approach, and it shows that the bigger the challenge, the more we need each other.

Stay safe out there!